Does adolescence really last until age 32?

Those “turning points” in brain aging aren’t quite what you think

TL;DR: Measuring differences across people of different ages at one point in time is not the same as measuring the process of aging or changes in the same person. Age gradients and apparent “turning points” can also reflect how generations differ, not just how brains change within individuals.

Judging by the engagement on my LinkedIn rant, I’m not the only one.

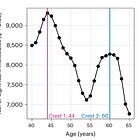

A recent study published in Nature Communications claimed that the wiring of the human brain changes in four distinct “turning points” across the lifespan, around ages 9, 32, 66, 83.

Queue the made-for-social media headlines:

These headlines certainly got my attention. Besides wondering if we should let anyone under age 32 get married or have kids, it seemed my twenty-something kids might have a lot more adolescence ahead of them than I bargained for.

But I also read the headlines with a bit of side eye—these “turning points” reminded me of a paper last year about “bursts” of biological aging at specific ages, which I didn’t find particularly convincing, because they didn’t actually measure aging.

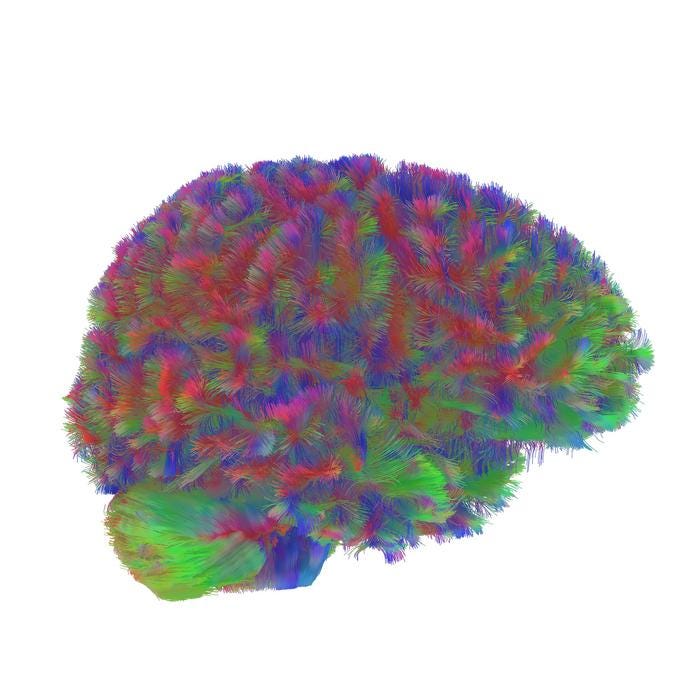

But as the curious data nerd that I am, I dove into the paper ready to learn something new. Indeed, I learned some cool things about how we study the brain, like mapping neural connections by tracking how water molecules move through brain tissue. These MRI “diffusion” scans measure how different parts of the brain are physically connected. Using statistical tools related to network science, researchers can then describe features of those brain connections, such as density, intregration and efficiency. Pretty amazing stuff that makes for some pretty pictures too:

A representative MRI tractography image of the first era of the human brain, ages zero-nine. Credit: Dr Alexa Mousley, University of Cambridge

This is all fascinating and important foundational work to better understand the structure and function of the brain. But how does the study go about using these cool new measures to characterize brain development across the lifespan?

Spoiler alert:

➡️ The study did NOT follow the same people over time as they aged.

➡️ The study compared the brains of different people aged 0 to 90.

This may sound like a small distinction, but it can make a big difference to the proper interpretation of findings.

Age differences ≠ aging

Researchers analyzed brain scans from around 4000 people, ranging from newborns to 90-year-olds. They then took all the measurements from the imaging data and used fancy statistics to distill it into more manageable variables that describe patterns in brain connectivity. Comparing those patterns across the people in their sample, they identified four major “turning points” in patterns of brain organization, around ages 9, 32, 66, and 83. Each brain “era” had distinctive features. For example, the “adolescent” era between ages 9 and 32 stood out for the rapid efficiency of the connections across the brain, whereas the brains of older adults had more stable architecture.

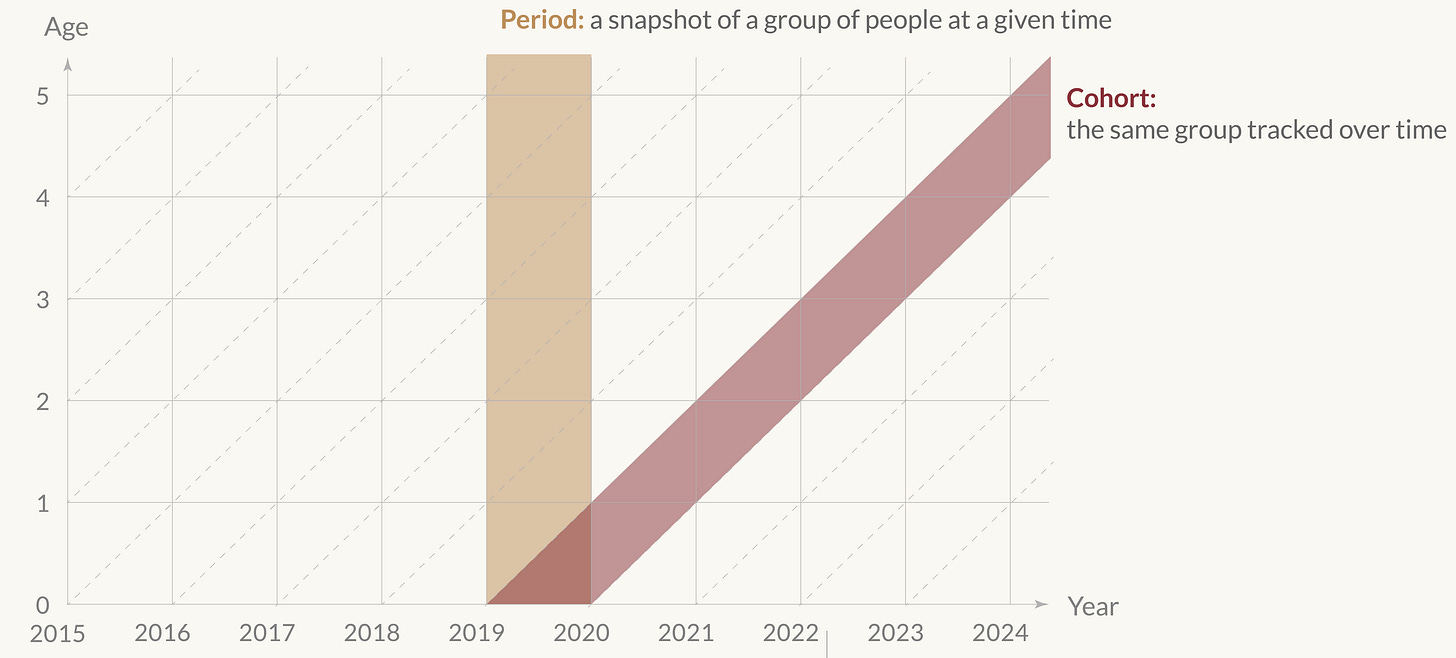

But…remember that the study was cross-sectional, not longitudinal. This is like capturing a snapshot of the brain at one point in time, rather than watching a time-lapse video.

Specifically:

People of different ages were scanned once

The authors then compared 5-year-olds, 30-year-olds, and 80-year-olds, etc to each other

They did not follow the same individuals over time

A visualization of cross-sectional vs. longitudinal data by age. Source: Our World in Data

So what’s the problem?

Calling these ages “turning points” strongly implies that individuals experience a developmental transition in brain organization at these moments. But cross-sectional data can’t show that.

As demographers and other population scientists love to obsess over, “age” effects are often more complicated than they seem.

In this case, we are especially concerned about potential “cohort effects.” Cohorts are people who were born around the same time and had specific generational experiences that they carry forward as a group (like exposure to leaded gasoline, or the adolescent brain re-wiring I experienced from making mix tapes from the radio, memorizing dozens of phone numbers, and watching The Goonies a hundred times).

Each generation had its own specific shocks to brain development

Especially in the last hundred years, our childhood environments have changed dramatically. Life expectancy has skyrocketed, thanks especially to reductions in infant and childhood mortality. Older generations were exposed to much more infectious disease, undernutrition, and brain-harming environmental exposures like lead compared to younger generations. Improving conditions helped our longevity AND our brains.

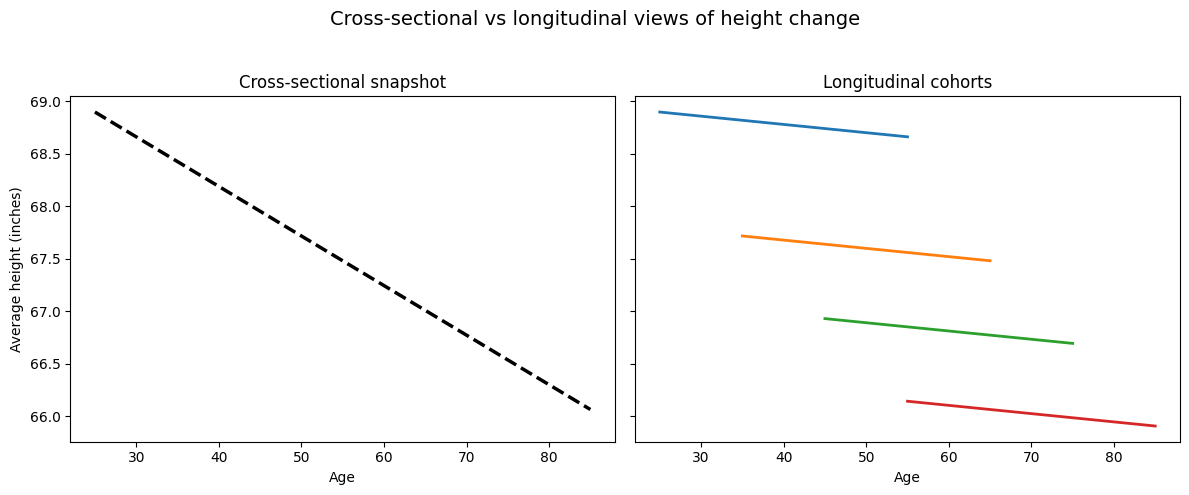

These better early-life conditions can be seen in the steady increase in average adult height, which has increased by almost 4 inches (10 centimeters) globally over a hundred years. Height provides a simple example of how interpreting “age effects” from a snapshot of people at different ages can be misleading.

Stylized illustration

In the righthand figure, the colored lines correspond to cohorts of people born around the same time whose height is measured over time. While people get a little bit shorter with age through spinal compression and loss of bone density, they don’t shrink as dramatically as the top figure would suggest.

A similar cohort pattern was observed for cognitive test scores. For decades, cross-sectional studies suggested that measurable cognitive decline begins in early adulthood and proceeds steadily thereafter. But when the same individuals were followed over time, that story proved wrong. Many cognitive abilities remained stable well into midlife, and some improved. As with the example of height, the apparent early decline turned out to reflect cohort differences in education, test familiarity, and life experiences. The cross-sectional age-associations were real, but the “developmental” narrative was wrong.

So, why do studies/headlines keep doing this?

To be fair, the authors acknowledge this limitation (briefly and buried) in their discussion:

“Moreover, the cross-sectional design of this project, due to the limited availability of longitudinal lifespan datasets, limits exploration of causality or temporal dynamics within an individual.”

But the title, abstract, and discussion (not to mention press coverage) still lean heavily on the language of development, aging, and “change.” The first line of the discussion section states for example:

“Our results emphasize the complex, non-linear topological changes that occur across the lifespan....”

Why the linguistic sleight of hand? Admittedly, it’s very hard to get lifespan brain data that follows the same individuals over time, especially with relatively new scanning technologies. We’d have to wait a hundred years to get an equivalent that measures how an individual’s brain changes over the lifespan. But we can still learn a lot about how important cohort differences are by following people for several years to see if those inter-individual change patterns match the cross-sectional data. So luckily we don’t have to just throw up our hands and say it’s impossible to estimate age effects. But we should be aware and communicate transparently about the proper interpretation of data like this. We can also look for opportunities to test and improve such estimates with longitudinal data that includes overlapping cohorts (different generations observed when they are the same age).

Given how common it is to see this type of misinterpretation, I think some of this reflects a natural tendency by scientists (but especially university press offices and journalists) to make the findings as interesting and relevant as possible. “Adolescence lasts until age 32” certainly makes for better cocktail party conversation than the more accurate “the brains of people at different ages look different, possibly from the passage of time but also because of the specific things experienced by people born in 1995 compared to 1965.”

I also think this reflects the orientation of different types of scientific training. Lab-based scientists have extremely deep knowledge of the biological phenomenon they are measuring at the molecular level, but aren’t necessarily accustomed to thinking about population-level dynamics. On the other hand, the challenge of age-period-cohort is seared into the brains of population scientists who work with large datasets that follow people over time and applies to almost any health and social outcomes. It often takes seeing the importance of cohort effects in your own data first hand to have that internal red flag go up with these types of cross-sectional “aging” effects.

Of course population scientists have our own blind spots, so this is not a failure of lab science, just a reality of scientific specialization. But I do think this is a good example of why interdisciplinary science is so important, where complementary training can help see the data from different perspectives and avoid common pitfalls from any one discipline. The better we get at peering deep into our biology, the more we need collaborations that can bridge the understanding of molecular and population data to put that biological data into real world context.

OK I get it. But is it really such a big deal to call this “aging”?

In any one paper, this type of linguistic imprecision may not be egregious. But I worry that persistent misframing can become misleading, especially to general audiences. When age differences from cross-sectional findings get discussed as biological milestones, readers start to infer personal meaning and an underlying ticking clock that the data can’t support. Whether this is good or bad I guess depends on your point of view…

More caveats

While I was most intruiged by how this study conflates age differences with “aging,” there are other methodological caveats to keep in mind as well.

There is little information on the characteristics of study participants, who come from different brain imaging studies carried out the UK and US. In most such volunteer studies, the participants tend to be healthier and more socioeconomically advantaged than the general population, meaning we are not capturing the full range of variation in brains (not to mention these are wealthy countries and not globally representative). This may seem unimportant, but previous work has shown that seemingly “universal” neuroscience findings based on convenience samples can lead to incorrect conclusions and point to the need for more representative samples in neuroscience research.

This is a very different methodological point, but even if these turning points reflected experiences of change in real people, they would be averages, with lots of variation for specific individuals. So nothing about these “turning points” would say much about what happens to you personally (like the average height in the population might not tell us a lot about your height).

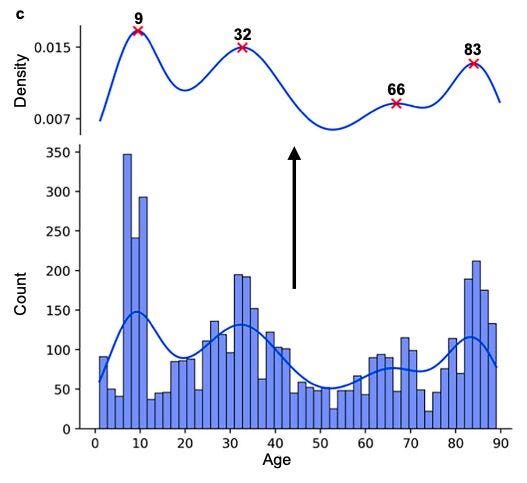

Turning MRI brain scans of the movement of water molecules into interpretable data is not easy and requires a lot of statistical assumptions. Adam Kucharski did some quick checks and found you can get different age “turning points” with slightly different (and probably more appropriate) modeling assumptions.

Again this does not mean that the analyses is incorrect in identifying some non-linearities in the statistical features they measure, just that we shouldn’t hang on too tightly to these specific ages and let the new conventional wisdom become “adolescence lasts until age 32.”

The Bottom Line

With new technology that allows us to peer into the brain “connectome,” describing age patterns as this study has done is an important descriptive step. There seem to be non-linear age patterns in brain network organization at the population level. That’s worth knowing and understanding further. But this paper doesn’t show that human brains pass through discrete developmental “eras.”

When we talk about aging, development, or decline, we should be clear about whether we’re describing how populations differ or how people change. Trust me, the demographers in your life will thank you!

The brain clearly loses it’s ability to make memes as it gets older

Stay well,

Jenn

![r/dataisbeautiful - Meme creation by age group: Intuitive, but interesting [OC] r/dataisbeautiful - Meme creation by age group: Intuitive, but interesting [OC]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!LrlL!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fbc09bfce-3e3e-4151-b80f-05675def93ba_2898x2025.png)

Thank you for another fascinating piece. As a 66 year old I am quite relieved by Professor Kucharski’s observations.

Hi Jenn,

Your article makes many important points regarding mixing cohort effects with developmental patterns. But I worry that it oversimplifies the discussion around cognitive performance and aging.

Specifically, there's a serious concern that longitudinal studies are distorted by practice effects in the cognitive assessment tasks. When you account for that, the results of cross sectional findings hold much better. See for example https://psycnet.apa.org/manuscript/2018-45562-001.pdf