From Mono to MS: When a Common Virus Goes Rogue

The “kissing disease” isn’t as innocent as it sounds

I previously covered the many ways infections and chronic diseases are connected, including to cancer, cardiovascular disease, and cognitive decline:

I promised some specific follow-ups, so today we’re diving into a compelling (and unsettling) example: a potential long-term downside to the so-called “kissing disease.”

For decades, researchers have suspected that Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), best known for causing infectious mononucleosis, might also be involved in triggering Multiple Sclerosis (MS). In 2022, we got the strongest evidence yet that this isn’t just coincidence.

What is EBV?

EBV is a herpesvirus that causes infectious mononucleosis (aka “mono” or “glandular fever”). Symptoms often include sore throat, swollen glands, fever, and crushing fatigue. Like its herpesvirus cousins (e.g., varicella zoster (causing chickenpox/shingles) and HSV-1 (causing cold sores), once you’re infected, EBV sticks around for life, lying dormant in your B cells with occasional potential flare-ups, particularly in times of immunosuppression.

Epstein-Barr Virus (Source). A photo that might deter some teenage kissing?

The “kissing disease” nickname for mono comes from its primary mode of transmission—saliva—and its prevalence in teens and young adults. But it can also be spread through shared utensils, drinks, or toothbrushes. EBV is incredibly common-by age 30, over 90% of the population is infected. Infected children often have few or no symptoms, but getting infected for the first time as an adolescent or young adult is more likely to lead to mono.

What Is Multiple Sclerosis?

MS is an autoimmune disease where the immune system mistakenly attacks the protective myelin sheath around nerve fibers, interrupting communication between the brain and the rest of the body. This can lead to numbness, muscle weakness, vision issues, and difficulty walking. Some people experience intermittent relapses, while others face a progressive decline. There’s currently no cure, but some treatments can help manage symptoms.

In the U.S., MS is most common among white women aged 55–64, where prevalence can reach nearly 1% in that group (842 per 100,000 people):

Source: Hittle M, Culpepper WJ, Langer-Gould A, et al. Population-Based Estimates for the Prevalence of Multiple Sclerosis in the United States by Race, Ethnicity, Age, Sex, and Geographic Region. JAMA Neurol. 2023;80(7):693–701.

What’s the EBV–MS Link?

An infectious trigger for MS has been suspected for well over a century. In the 1980s, scientists found higher levels of EBV antibodies in people with MS compared to healthy controls. But correlation isn’t causation-it wasn’t clear if EBV caused MS, or if people with MS just had different immune responses in general. And of course, we can’t ethically randomize people to get a virus, so researchers had to lean on evidence from other types of research designs.

In 2022 researchers published a massive study of over 10 million active-duty U.S. military personnel with baseline blood samples upon military enrollment. About 5% of the sample were EBV-negative at baseline. Given the large overall numbers, this was a rare but golden opportunity to track what happens next.

The study found that among the 801 people who later developed MS:

Only one was EBV-negative throughout.

35 were EBV-negative at baseline, but all but one became infected before MS onset.

This corresponded to a 32.4X higher risk of MS following EBV infection.

In epidemiology, we get “excited” about 1.5X or 2X risk increases. A 32X increase is MASSIVE. An effect size that strong is unlikely to be just due to random chance. Any unobserved “confounding” variable that might cause both EBV and MS would also have to be extremely powerful to explain this effect. That’s not impossible, but unlikely.

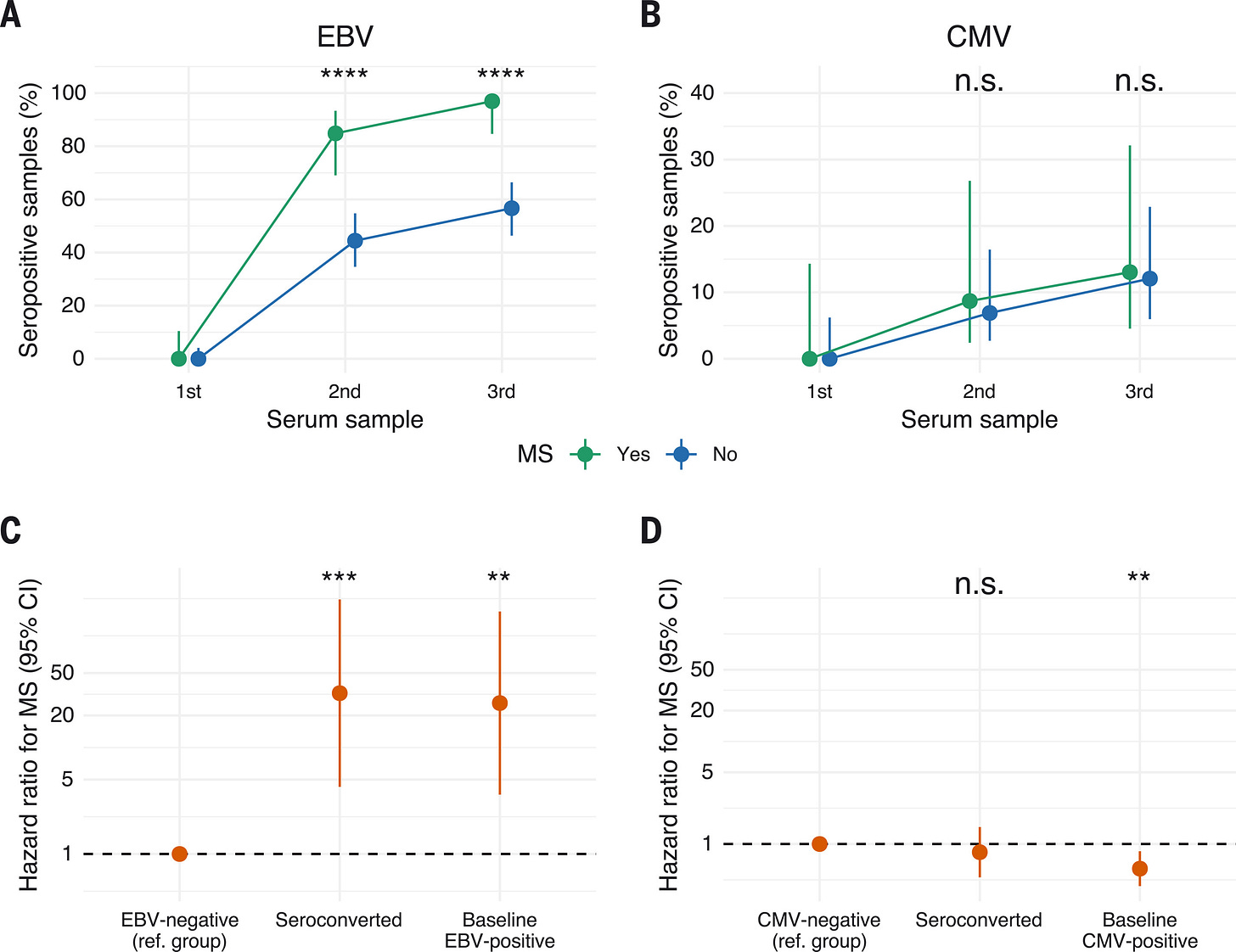

EBV infection precedes MS onset and is associated with markedly higher disease risk. Source: Fig 2, Kjetil Bjornevik et al. Longitudinal analysis reveals high prevalence of Epstein-Barr virus associated with multiple sclerosis Science 375,296-301(2022).

Ruling Out Other Explanations

Because this is an observational and not randomized study, the researchers also did a bunch of other checks to bolster our confidence in cause and effect. Maybe this result really reflects a general susceptibility to viral infections that is also correlated with MS? Or perhaps pre-clinical MS increases your susceptibility to infections (aka “reverse causality”)? To try to rule this out, researchers used cytomegalovirus (CMV), another herpesvirus transmitted similarly, as a “negative control.” Unlike EBV, getting CMV infection over the follow-up period didn’t raise MS risk, which was reassuring.

The researchers also did a deeper dive, testing for over 30 viral infections at the same time. Only antibodies against EBV were higher in MS cases compared to controls. This strengthens the evidence that the result isn’t just about immune dysfunction in MS patients, it’s something specific to EBV.

Overall, this study provides as close to definitive evidence as we are likely to get about a causal link between EBV and MS.

Researchers have proposed several mechanisms through which EBV might trigger the autoimmune reaction seen in MS. One leading theory is molecular mimicry-EBV proteins, especially EBNA1, resemble components of myelin (the protective coating on nerve fibers), confusing the immune system into attacking the body’s own tissue. Research into these mechanism is on-going.

Source: William H. Robinson, Lawrence Steinman. Epstein-Barr virus and multiple sclerosis.Science375,264-265(2022).

It’s important to note that nearly everyone is infected with EBV, but only a small fraction develop MS. This means that infection with EBV is likely to be necessary, but not sufficient, to trigger the development of MS. Other risk factors, like genetic susceptibility, may interact with EBV to cause MS, or the infection may trigger the disease randomly in a small fraction of people.

What This Means for MS Prevention and Treatment

It’s not ideal to learn that a super-common childhood virus may help trigger a lifelong neurological condition. But it could be incredibly helpful in moving toward solutions.

Anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies (like ocrelizumab) deplete B cells-the cells that harbor latent EBV-and have shown success in treating MS.

Antivirals that treat EBV directly may slow clinical progression of MS.

EBV vaccines have been in development for many years, but we aren’t there yet. Ideally they will offer promise for prevention of MS.

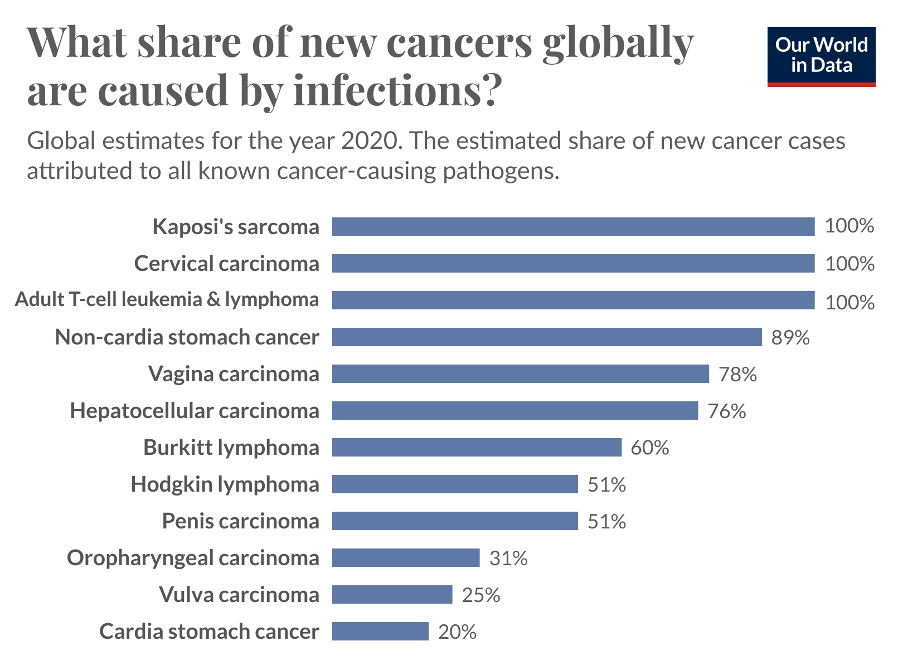

The case for a potential EBV vaccine is even stronger because the virus is also linked to Hodgkin lymphoma, Burkitt lymphoma, and nasopharyngeal cancer. There’s even emerging evidence that EBV may be reactivated during COVID-19, possibly contributing to autoimmunity and long COVID.

Bottom Line: Infectious Disease ↔️ Chronic Disease

The story of EBV and MS is a powerful reminder that the line between infectious and chronic disease is not as sharp as we once thought, and of why infectious disease research deserves sustained investment.

Just as the HPV vaccine prevents cancer, a vaccine that prevents MS would be nothing short of miraculous.

Stay well,

Jenn

In Case you Missed It:

More Than a Fever: Infections and Chronic Disease

Data for Health is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Many cases of ME/CFS are also associated with EBV.