Is our population collapsing?

Throwing some cold water on "population panic"

TL;DR: The World and US populations are still growing, not declining.

You may have heard (perhaps from a certain tech billionaire) that “population collapse” is currently the biggest threat facing humanity.

Luckily, there is a whole academic discipline that studies such things:

“Demography”

from demo- (“people”) + -graphy (“written representation of”)

I got my PhD at one of the oldest demographic training programs in the world, Princeton’s Office of Population Research, and I am currently Deputy Director of the amazing Leverhulme Centre for Demographic Science at Oxford.

All of this is to say… Demographers are my people.

Demographers never get sick of this joke.

Naturally I get A LOT of blank stares when I say I am a demographer; it’s not the easiest academic subject to define. So consider this the first in a series of my attempts to improve the understanding of this amazing but underappreciated discipline.

Demography is the statistical study of human populations. While this may sound boring as hell, in fact demographers measure and analyze how populations change due to the most intimate human experiences including birth, parenthood, migration, and death. Demography also tells the story of the history of humanity, such as how it took most of human history for our population to reach 1 billion—and just over 200 years to reach 8 billion. (I know I am biased, but this is fascinating stuff)!

Are demographers worried about “population collapse”?

By and large, no. It’s a fascinating topic to be sure, one that is worth more than one post (so stay tuned).

But we’ll start with some basic demographic facts:

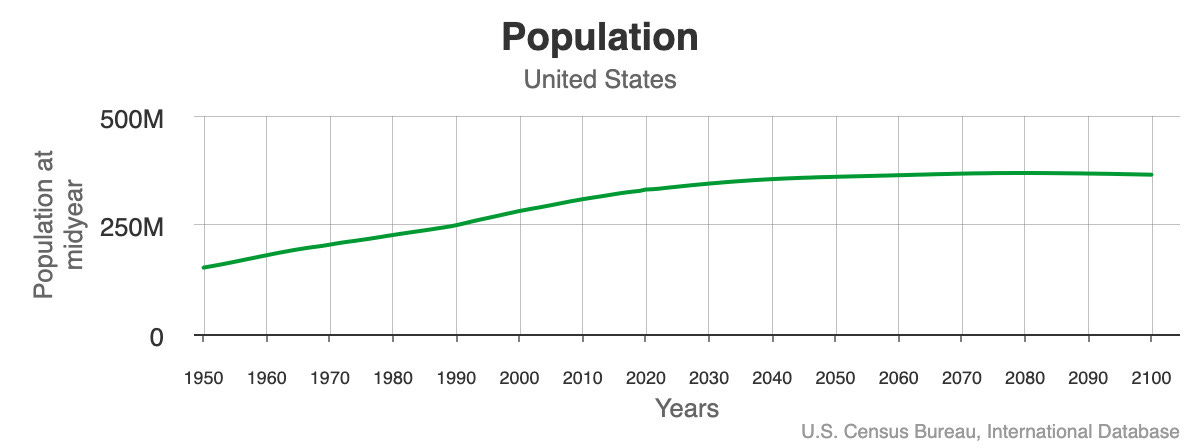

The US and World populations are projected to continue growing until around 2080, with the US adding over 30 million people (and the World adding more than 2.5 billion people).

Source: US Census Bureau International Database

I don’t know about you, but that doesn’t feel like “collapse” to me.

After hitting this “peak,” population is expected to plateau or decline slowly, not collapse.

Some countries have already reached their “peak” population, but declines will happen relatively slowly. For example Portugal is projected to decline from a population of 10.4 million to 9.8 million by 2050 and 8.8 million by 2100. China’s population has already peaked and may fall faster, but is still expected to have around 1 billion people in 50 years. Of course projections can be wrong, and we adjust them every couple of years based on what actually happens. But demographers are pretty good at projecting population size several decades into the future— because we know the number and ages of all the people already alive, the ones that will contribute to births and deaths for the next few decades. Populations have “momentum” (and “echos”) because the number of women at reproductive ages today drives the potential number of babies. So even when birth rates drop, populations keep growing. It’s projecting beyond fifty years that starts to get dicey, yet it’s that more distant future that fuels the fear of “population collapse.”

But what about falling birth rates? Don’t we desperately need more babies?

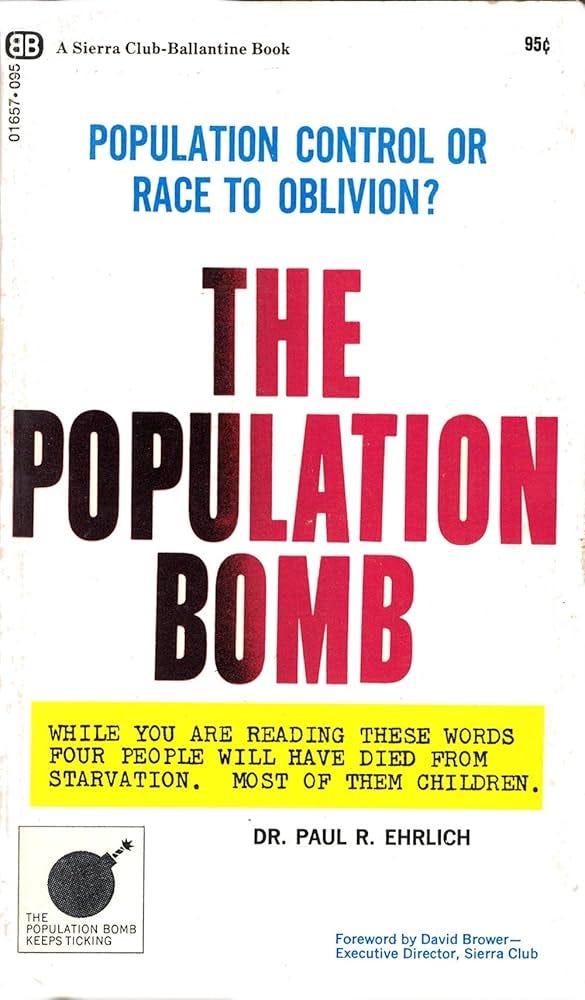

Birth rates have fallen dramatically around the world, from an average total fertility rate or “TFR” of close to 5 children per woman globally in 1950 to around 2 children per woman today. This drop is what led us from the panic about the “population bomb” in the 1960s to the slower population growth we have today.

It’s also true that the fertility rate in many countries has fallen “below replacement,” roughly two children born per woman (because population size stabilizes in the long run if a woman replaces herself and her partner).

But the total fertility rate can be deceptive. The TFR is a “snapshot” of fertility in a given country each year, but it’s not the experience of any real woman. The TFR estimates how many kids a pretend woman would have if she passed through her reproductive years having babies at the current age-specific fertility rates in this year. (You may be a true demographer if you recognize the similarity between how we calculate the TFR for fertility and how we calculate life expectancy for mortality, which summarizes age-specific mortality rates for a “synthetic” rather than real cohort).

When people start having babies later, this can make the TFR look artificially lower. Since 1980, the median age at first birth for US women increased from 22.6 to 27.9 years. So those babies not born to 22-year-olds make the fertility rate look lower, and it takes a few years for those “delayed” babies to show up in the higher fertility rates of 28-year-olds, thus a lower TFR.

The only way to know for sure what is happening with fertility is to wait until the end of a woman’s reproductive life (around age 45-50) and measure how many children she actually had (called “completed fertility” or “children ever born”).

From this lens, fertility in the US is much more stable and close to “replacement” compared to the TFR:

Of course, only time will tell whether women currently in their 20s and 30s today are deciding to delay or ultimately have fewer babies (a huge decision they should always have the right to make). But based on what we can see from women who’ve finished their childbearing, the fertility decline in the US is not as dramatic as it seems (which means population stabilization rather than decline).

Population realism

The World population will still likely add over 2 BILLION people over the next 50 years before stabilizing at 10-11 billion. Fifty years ago, we had a mere 4 billion people on Earth and were terrified of mass starvation due to the “population bomb.”

Human societies proved more adaptable than expected back then, and my hunch is that we are again underestimating our species ability to adapt to this new demographic future. Certain countries and regions will see populations change more quickly with resulting challenges, as they did during the period of unprecedented population growth. Humans have migrated literally forever, and despite the political challenges migration will continue to play an important role in societal adaptation to population change in the long run.

Population aging (a higher proportion of the population at older ages relative to younger ages) will bring social and economic challenges, but manageable ones. Population aging also won’t last forever—it’s a demographic anomaly arising from the combination of large baby boomer cohorts and falling fertility thereafter which will eventually stabilize as generations become more similar in size. What’s more, having a sudden baby boom now would not save Social Security. This is because babies born today are dependents and are net drains on the economy for a good 20-30 years, well after the retirement funding crunch of the Baby Boomers has passed.

“In demography, the future is already here. No policy can increase the number of babies born yesterday.” -Phil Cohen

But will long-term human fertility stay below “replacement”?

Predictions (especially about the future) are hard. This means we should be *very* humble about our ability to predict trends in human behavior more than fifty years out, especially about something as personal as childbearing. The whiplash from “population bomb” to “population panic” should have taught us that. We have no idea how humans in 2100 and beyond will choose to live their lives. But social engineering designed to change this unknown distant future is bound to fail, at potentially high human cost.

Public policies to boost birth rates historically don’t work (or have small effects), but can have serious negative effects on reproductive and human rights. There is a lot more to say about this, but for now suffice to say that we can have social policies that support families by increasing people’s well-being and choices in life, without regard to whether such policies increase the national birth rate.

So this demographer’s take: don’t panic about birth rates. Instead, let’s invest in the education, health, and happiness of the 8 billion precious humans alive now and the billions more still on the way in our lifetimes.

Stay well,

Jenn

For deeper dives into what demographers think about the current “pro-natalist” movement, some links:

The problem with pronatalism: Pushing baby booms to boost economic growth amounts to a Ponzi scheme, The Conversation

Follow demographer and fertility expert Karen Guzzo and read her recent interview.

The Low Fertility Fallacy, Foreign Affairs

Pro-natalism won’t work… by Phil Cohen

Changing the perspective on low birth rates: why simplistic solutions won’t work, BMJ

Population decline: Towards a rational, scientific agenda, Special Issue of the Vienna Yearbook of Population Research

Good for you, Jenn, for addressing it head on! (My spouse has a good explanation for what I do. I use it almost every time I introduce myself as a demographer. As he says, "Demographers study people being born, people moving, and people dying.") I usually go on to explain that I focus on the people dying part. That is my research is focused mostly on health, aging, and mortality

OMG, in high school all we heard about was how 'overpopulated' the world was and how birth rate needed to slow down. Then our corporate overlords began to panic and fear-mongered the falling birthrate. But the population is still growing!!