Summer reading: How do we know something is true?

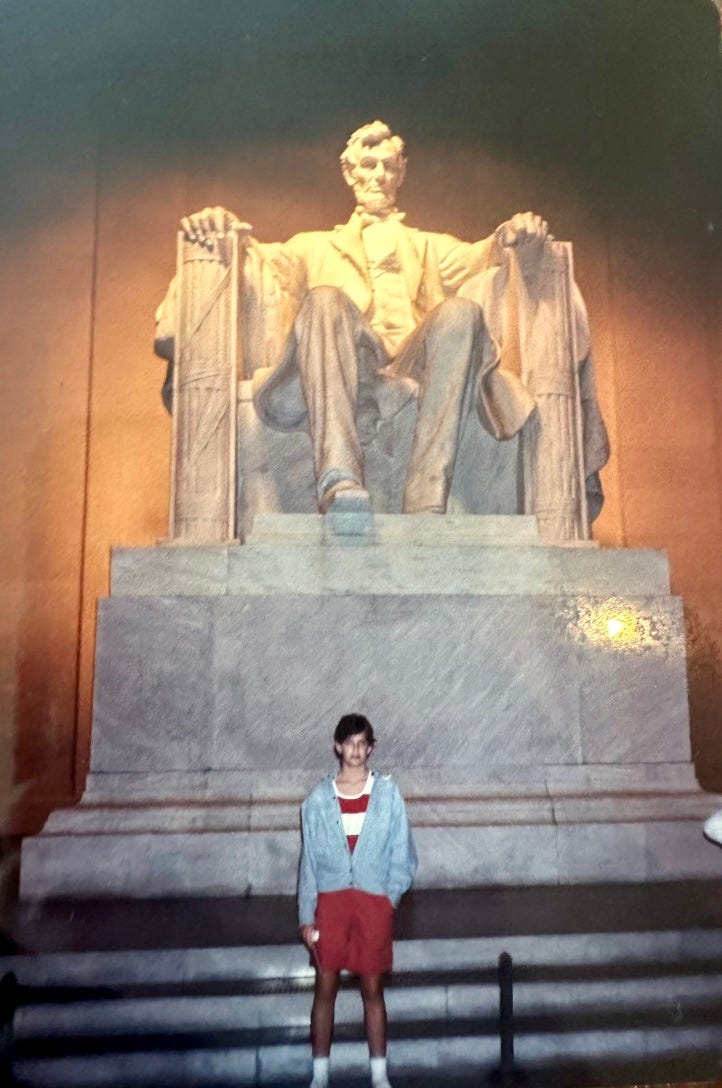

“Proof” that my childhood obsession with Abraham Lincoln was warranted

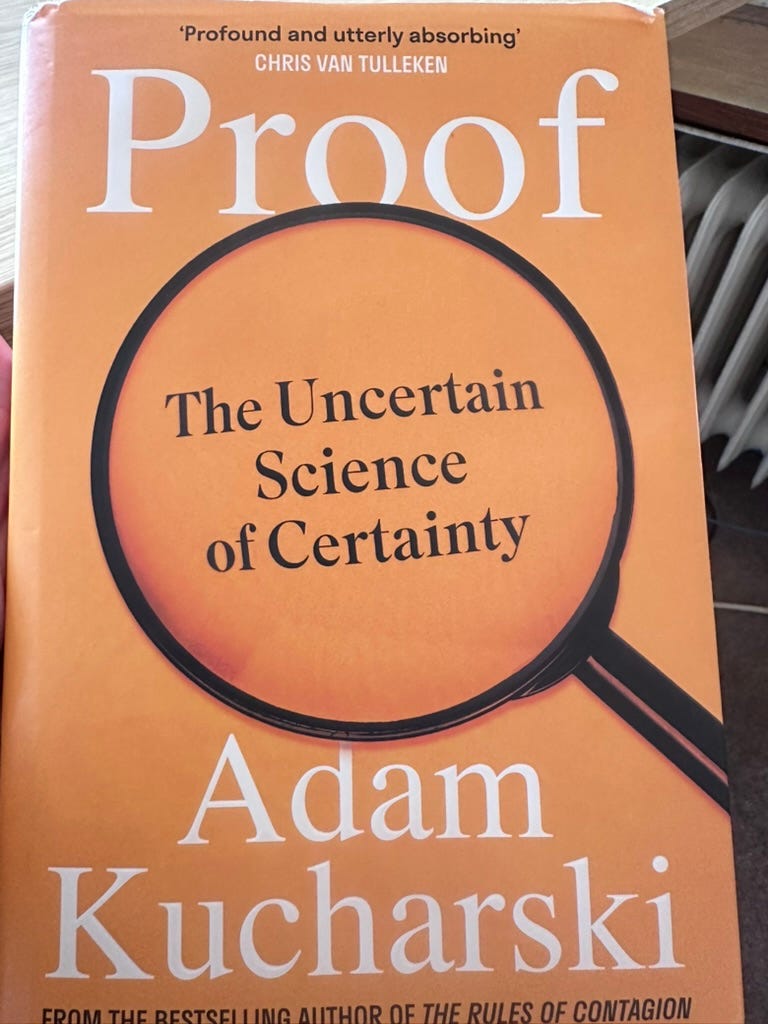

Not my usual content, but I wanted to give a quick shout-out to the book “Proof” by

for those looking for some timely and thoughtful summer reading.In the current moment of debates about what feels like “settled” science, such as the safety and efficacy of vaccines, this book really resonated with me. While there is a lot we can do to build scientific evidence, “proof” is ultimately a social process.

I honestly don’t read much for “pleasure” given how much I read for work…but bringing “Proof” along on a holiday was a real treat.

You had me at Abraham Lincoln

I doubt Kucharski knew that I was legit obsessed with Abraham Lincoln as an adolescent (but my family and friends can attest). But his description of Lincoln’s own obsession with mastering the principles of logic made me think about my intense interest in a new light. Perhaps Abe was the first time I instinctively “found” my data-driven people-a great mind dedicated to careful thinking, in the service of making the world better.

Before I had ever heard about statistical inference, using logic and precision in words to make an argument seemed like the Holy Grail. I can still recite the Gettysburg Address by heart, where Lincoln reframed the American Founders’ “self-evident” truth as a “proposition” that all men are created equal…a proposition that Kucharski points out required social action to be made true.

My Lincoln Memorial pilgrimage at age 12. Don’t judge 😂

Kucharski takes the reader on an immersive historical journey starting with Euclid that prompts us to reflect deeply on how we know things. I loved learning for the first time how the English obsession with the perfect cup of tea led to an important insight for statistical inference (spoiler alert: put the milk in the cup first).

Later in the book, Kucharski draws heavily on his own experience as a scientist during the COVID-19 pandemic who was closely involved with epidemiological modeling and forecasts that helped inform government policy in the UK. This part of the book resonated with me so much, particularly in the current polarized public health climate. With oversimplified and revisionist histories of the pandemic making the rounds, Proof reminds us of the messy reality of those times and the difficult decision-making under uncertainty that is way too easy to criticize in hindsight.

Kucharski suggests that it is getting harder to demonstrate “proof” due to the complexity and specialization of science. This meant that during a crisis like COVID, scientists had to spend too much time debating reality rather than policy. This highlights a fundamental tension I am struggling with: how can scientists effectively communicate important evidence (and all the uncertainty that accompanies it) in the face of organized dissemination of dishonest information aimed at undermining trust? Some lines from the book that particularly resonated on that point (from the Chapter “Big Lies”:

“The pressure to believe a falsehood is often social.”

“Taking the contrarian view can also be an opportunity to claim intellectual superiority.”

“To function properly, systems of science, justice and democracy all require an ability to agree on what is true and what is false.”

Kucharski’s discussion of “triangulation” of evidence is highly relevant today, for example current discussions in the US about who can benefit from COVID vaccines, which I recently wrote about here:

Do additional COVID vaccines really help?

If you missed Part I, please go back to read why I think there is compelling evidence that kids can benefit from regular COVID vaccines. We need to talk about this more often, because take-up has been low in the US (much lower than annual pediatric flu vaccines), despite universal recommendations. While I’m emphasizing the importance of vaccines for kid…

I am clearly not a professional book reviewer, so I fear I am not doing this book justice. But Proof is some fantastic writing from Adam and a highly recommended read for history, philosophy, and data nerds alike!

For more, you can also listen to this recent interview between

and :Happy summer reading!

Jenn

I guess every scientist implicitly understands the distinctions of hypothesis and theory, and the impossibility of proof. Along with that they learn how to walk that path of treating a theory as a solid foundation for future work whilst being simultaneously open to the knowledge that it is open to replacement and doubt. Even if you work on quantum gravity you still treat quantum mechanics as a reliable description of the world.

I have been following Philosophy of Science discussions for a while now and what strikes me is their totally dogmatic approach to questions around proof and the status of theories. Most of the people seem to be in the USA, and I wonder if the literal approach to christianity that is found there may spill over into other aspects of life. Do people there subconsciously expect scientists and their theories to provide an infallible picture of the world, and consequently reject them when it turns out to be just a working model.

I particularly appreciate this:

"Perhaps Abe was the first time I instinctively “found” my data-driven people-a great mind dedicated to careful thinking, in the service of making the world better."

My version: We need the truth, whatever that turns out to be, and not just beliefs, to make the world a better place. Sincerely seeking the truth is a big challenge.