Can the RSV vaccine also prevent dementia?

Some intriguing but not definitive new data

TL;DR: A new study found that an adjuvant (immune-enhancer) in both the RSV and shingles vaccines may reduce the risk of dementia, but the findings are more suggestive than conclusive.

It’s been an exciting few months for research on vaccines and dementia. In April, I wrote about a study using a cool natural experiment to show that shingles vaccination reduced the risk of dementia in older people in Wales, followed by a similarly designed confirmatory study with Australian data.

These studies provided the strongest evidence yet for long-suspected links between infections, immunity, and dementia. But they couldn’t say much about the biological mechanism by which the shingles vaccines might reduce dementia risk, and they evaluated the older and less effective version of the shingles vaccine, Zostavax.

A new study using data from the US found that both the newer shingles vaccine and the new RSV vaccine were associated with a reduced risk of dementia diagnoses over up to 18 months of follow-up.

The authors of this study previously found a reduction in the risk of dementia for those receiving the newer protein-based Shingrix vaccine compared to the previous live-attenuated vaccine Zostavax. They hypothesized that it might be the adjuvant used in Shingrix that makes the difference.

In vaccines, an adjuvant (or “helper”) is something added to boost the immune response to make it stronger and longer-lasting. The AS01 adjuvant used in both Shingrix and the new RSV vaccine (Arexvy) includes two immune-stimulating components that enhance both innate (immediate) and long-term (memory) immune responses. Some of the immune responses induced by the AS01 adjuvant have been shown to reduce amyloid plaque deposition (a hallmark of Alzheimer’s) in mice and are associated with slower cognitive decline among older adult (humans).

The new study compared older people who received one or both of the AS01 adjuvanted vaccines (Shingrix or RSV) to similar people who received only the flu vaccine. The sample included close to 500,000 people drawn from electronic health records in the US, with an average age of 72. People could have had the shingles vaccine much earlier, so here the follow-up “clock” only started when people got or were eligible for the RSV vaccine, beginning in 2023.

Key results:

📌 People who received the RSV or Shingles vaccine had a lower risk of dementia over the follow-up period compared to people who only had the flu vaccine.

📌 The reduction in risk was similar whether they received one or both of RSV and shingles vaccines, meaning the effects did not seem additive

📌 The results were similar for both males and females (unlike some previous studies)

Source: Taquet, M., Todd, J.A. & Harrison, P.J. Lower risk of dementia with AS01-adjuvanted vaccination against shingles and respiratory syncytial virus infections. npj Vaccines 10, 130 (2025).

How big were the effects? Worth paying attention to

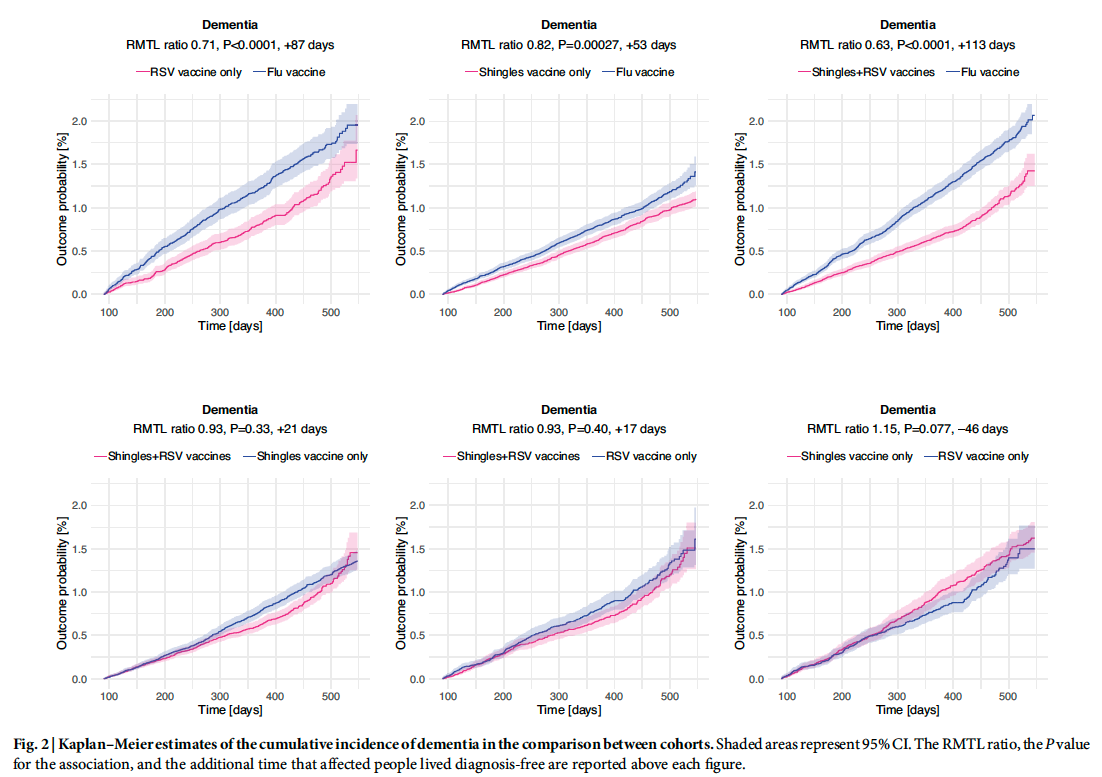

Receiving both the Shingles and RSV vaccines was associated with an average 37% more time spent without a dementia diagnosis over the 18-month follow-up period compared to those receiving only the flu vaccine. This corresponds to a probability of a new diagnosis of around 2.1% in the control group compared to about 1.3% of those in the RSV and shingles vaccine group (top right curve in Figure 2 above). While the absolute risk of a new dementia diagnosis over 18 months is (thankfully) low, the relative risk reduction was substantial. An important caveat is that since people were only followed for up to 18 months after vaccination, it’s hard to know whether this association reflects prevention of dementia or delaying its onset (good either way, but obviously we’d prefer to prevent entirely).

Is the study convincing? File under intriguing and worthy of follow-up.

Unlike the recent shingles vaccine and dementia papers I covered, this paper does not take advantage of any “natural experiment” to mimic randomization of who gets the vaccine. This means that everyone who got the RSV or shingles vaccine chose to get it, and people who choose to get vaccines may be different from people who don’t in ways that are correlated with health risks like dementia. Theoretically, this bias could work in both directions. People who are very health-conscious may choose vaccination and be less likely to get dementia because they also exercise, don’t smoke, and get good sleep. On the other hand, people who are sicker may be more likely to get the vaccine precisely because they feel vulnerable. Either way, these underlying differences can make vaccines look like they are linked to dementia even if the vaccine doesn’t have a true “causal” effect.

The study works to address this causal inference problem in a few different ways:

🟢 The “control” group is older people who got the flu vaccine, rather than people who got no vaccines. The flu vaccine does not contain the same adjuvant as the RSV and shingles vaccine. But people who get the flu vaccine should be more like those who also get the RSV and shingles vaccine than people who get none of these vaccines, since they’ve shown a willingness to get a recommended vaccine. This is a good step in the right direction towards an “apples to apples” comparison, but we still don’t know why the “flu-vaccine only” people chose not to get an RSV or shingles vaccine...so they may still be different in some way from people who do.

🟠 To further address that concern, the study statistically “matches” RSV and shingles vaccine recipients to flu vaccine-only recipients who looked very similar to them based on other health and demographic data. Table 1 of the paper shows that this “control” group is very similar on lots of measured characteristics, such as age and pre-existing health conditions. While that is reassuring, with non-randomized studies we are more worried about any “unobserved” characteristics that are different in the two groups, so we can’t be 100% sure something else isn’t driving the results. Importantly, the dataset has limited information on the socioeconomic characteristics of the patients like their income or education, which is often strongly linked to both health behaviors like vaccine uptake and a wide array of health outcomes.

🟠 Finally, they check whether the RSV and shingles vaccines are associated with a “negative control” outcome. This is sometimes called a “placebo” control, meaning an outcome you wouldn’t expect to be associated with the vaccines. Here, the authors sum up several conditions, including acute appendicitis, pancreatitis, gallstones, and shoulder capsulitis. If RSV and shingles vaccines were associated with the negative control outcome, it may be a red flag that the results are “spurious” and just picking up that people who choose to get these vaccines are healthier in general than people who don’t choose to get the vaccine. The authors found no association of the vaccines with the combined negative control outcome (Figure 1, Panel A below). While this is reassuring, the supplemental table does show some evidence that the vaccines are associated with reduced risk for one of the individual control outcomes (acute pancreatitis). This could be just by chance, or it could be picking up this healthy vaccinee bias we are concerned about…so it raises a little bit of doubt in my mind, but it’s not really enough evidence to be sure either way.

Source: Taquet, M., Todd, J.A. & Harrison, P.J. Lower risk of dementia with AS01-adjuvanted vaccination against shingles and respiratory syncytial virus infections. npj Vaccines 10, 130 (2025). A ratio below 1 indicates a reduced risk.

The Verdict: Promising and a good basis for further research

Overall, the authors did most of what’s possible to bolster confidence in the causality of their findings within the constraints of the available data. But given the non-randomized setup of the data, even the most careful analysis leaves some room for concerns that something else is driving the results.

I like that this study draws attention to a particular mechanism through which vaccines may be neuroprotective, specifically the stimulation of the immune system via adjuvants. People who got the shingles vaccine were also less likely to get shingles (yay!), so part of this effect could work through reduced risk of infection rather than the adjuvant per se. For RSV the protective effect was seen quite quickly and likely can’t be fully explained by avoiding infection. This intriguing finding will hopefully lay the foundation (and justify the funding) for randomized trials that test this hypothesis and specific biological mechanisms directly, or perhaps for follow-up or re-analysis of existing clinical trial data using these vaccines.

The RSV and Shingles vaccines are already worthwhile; potential benefits for dementia are a bonus

The Shingrix vaccine is recommended for people ages 50 and over (or younger with compromised immune function) in the US. It is highly effective at preventing shingles, a painful and debilitating disease, so at this point, the potential benefits for dementia are a bonus. I for one was psyched to get this as a 50th birthday present:

The RSV (respiratory syncytial virus) vaccine was newly offered to older adults in the US (60 and over) as of 2023. The CDC currently recommends RSV vaccination for everyone 75 and over, and for ages 50-74 with risk factors. RSV causes a lot of nasty illnesses, hospitalizations, and deaths in older people (and very young children). So here again, getting the vaccine is already well justified based on reducing the risk and severity of infection alone, and any potential neuroprotection can be considered a bonus.

Note: In this study the authors couldn’t distinguish the brand of a person’s RSV vaccination, and only the Arexvy brand contains the adjuvant AS01, while Abryvso does not. The authors estimate that around 24% of RSV vaccinations would be from this non-adjuvanted brand, so if anything this would underestimate the benefits of the vaccine in their analysis if the adjuvant was the important mechanism.

Overall, I’m glad that connections between infections, the immune system, and the brain are getting more research attention. Given our limited toolkit against dementia, learning how the immune system may protect the brain is a promising avenue for potential interventions.

Stay safe, stay curious!

Jenn

In case you missed it:

Can the Shingles Vaccine Prevent Dementia?

You may have seen headlines about a fascinating new study in Nature suggesting that the shingles vaccine may lower the risk of dementia.

More Evidence That The Shingles Vaccine Reduces Dementia Risk

It’s only been a few weeks since a fascinating study showed that getting the shingles vaccine reduced the risk of dementia in older adults in Wales.

Some Good News! Dementia is trending down.

If it feels like a tsunami of bad news right now, I’m here to cheer you up with one trend that is moving in a positive direction.Data for Health is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Finally, a Blood Test for Alzheimer’s?

TL;DR: A less invasive test for Alzheimer’s is a big advance. But it’s not perfect, and is not meant to screen healthy people.Data for Health is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

That's something new thanks

I agree with your classing it as 'Intriguing file for further notice'. My worry over all such studies is that dementia develops so slowly and is subject to some diagnostic uncertainty that I never accept the results of a single study without coupled lab and human data.

If there is an effect then the adjuvant could very well be the effective agent. However, is there any evidence for a shingles - dementia link, either positive or negative?